Previously: Intro, Running Apple Pascal on a modern Mac, The Editor, The Filesystem, Text Files.

Part 4 – File Formats (Code)

Unlike text files, the code file format is well described in the Apple Pascal Operating System Reference manual. So decoding a code file should be really simple, right? Let’s take a very simple “Hello World” program as an example:

Program HelloWorld;

var

name: String[80];

begin

writeln('Enter your name:');

readln(name);

writeln('Hello, ', name);

end.If we run this through the compiler, we get a 1024-byte code file. That’s the minimum size for a .CODE file. What’s in that file? I’m so glad you asked!

Code File Structure

A code file is made up of a maximum of 16 segments, of various types. The USCD Pascal language has this concept of SEGMENTS, which are independent pieces of code that can be demand-loaded. You pretty much have to have something like this if you want to support complex programs on an extremely memory-constrained system. The Pascal compiler is almost 40 kB, for example. You would probably struggle to get the OS, compiler, and the program you’re compiling all into memory at once if you couldn’t load only part of it at a time.

But our HelloWorld program is very simple, so it’s just going to have one segment.

Segment Directory

The first block of the file is a directory to the segments, and the structure looks like this, translated from Pascal as given in the manual, to Rust:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy)]

#[repr(C)]

struct CodeInfo {

address: u16, // in 512-byte blocks

length: u16, // in bytes

}

#[repr(i32)]

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy)]

enum SegmentKind {

Linked, // A ready-to-run program

HostSegment, // The outer block of a Pascal program, if it has unresolved references

SegmentProcedure, // Not used.

UnitSegment, // A Unit, ready to be linked

SeparateSegment, // Native-code segment

UnlinkedIntrinsic, // An Intrinsic unit with unresolved references

LinkedIntrinsic, // An Intrinsic unit

DataSegment // Data segment - used for some intrinsics

}

#[repr(C)]

struct SegmentDictionary {

code_info: [ CodeInfo; 16], // one for each of 16 segments

seg_name: [[u8; 8]; 16], // 8 charcters, space-padded

seg_kind: [SegmentKind; 16], // one for each of 16 segments

text_addr: [u16; 16], // For Units, this points to the Interface section

seg_info: [u16; 16], // A bitfield for each segment

intrinsic_segments: u32, // One bit for each segment in System.Library

// This is "library information", which is described by the Apple Pascal manual thus:

// Library information of undefined format occupies most of the remainder of the segment dictionary block.

// That's...great. I guess we'll figure that out when/if it comes up

library_info: [u8; 140],

copyright_string: [u8; 80], // Copyright, as set by (*$C *), seems to be zero-terminated?

} //total size: 512 bytes When I originally implanted this, the address and length fields in CodeInfo were in the opposite order, based on how the structure was defined in the Apple Pascal manual. But they clearly are in THIS order. I eventually looked in the official public UCSD source code dump of the I.5 code, and it shows a declaration matching what I’m using above.

I guess this was just badly-transcribed into Apple’s manual. At least it was obviously wrong. I do wish the version I.5 source dump was a little better organized. It’s kind of difficult to figure out what each of those files is even supposed to be. Maybe that’s a project for another day.

Intrinsic Segments

My simple example doesn’t seem to touch on this functionality, at all. The Intrinsic Segments entries are all zeroes. But if I run my code file dumper against SYSTEM.LIBRARY, I get:

./target/debug/p-code --code-file tests/SYSTEM.LIBRARY list

Listing code file tests/SYSTEM.LIBRARY

File length: 19456

Segments:

Segment 0x0, name: LONGINTI, address: 0x600, length: 0x9f2, kind: LinkedIntrinsic, text_addr: 0x1, seg_info: "[unit: 30, type: Native code, version: 6]"

Segment 0x1, name: PASCALIO, address: 0x1400, length: 0x816, kind: LinkedIntrinsic, text_addr: 0x8, seg_info: "[unit: 31, type: Pcode, Little-endian, version: 6]"

Segment 0x2, name: CHAINSTU, address: 0x2000, length: 0x19a, kind: LinkedIntrinsic, text_addr: 0xf, seg_info: "[unit: 28, type: Pcode, Little-endian, version: 6]"

Segment 0x3, name: TRANSCEN, address: 0x2400, length: 0x4f4, kind: LinkedIntrinsic, text_addr: 0x11, seg_info: "[unit: 29, type: Pcode, Little-endian, version: 6]"

Segment 0x4, name: TURTLEGR, address: 0x3000, length: 0x146e, kind: LinkedIntrinsic, text_addr: 0x15, seg_info: "[unit: 20, type: Native code, version: 6]"

Segment 0x6, name: APPLESTU, address: 0x4800, length: 0x28c, kind: LinkedIntrinsic, text_addr: 0x23, seg_info: "[unit: 22, type: Native code, version: 6]"So unless I use one of those native-code intrinsics, I won’t be seeing any entries here. Makes sense.

Library Info

As the comment says, no idea what this is supposed to do. It seems to always be empty in the files I looked in.

Copyright

There are 80 bytes set aside for copyright info embedded in the header. You can set this with the (*$C *) compiler directive in a Pascal program:

(*$C Copyright Mark Bessey, 2025 *)

Program HelloWorld;

begin

writeln('Hello, World');

end.If you don’t specify a copyright, the area is filled with zeroes. I was only able to set a maximum of 79 characters of copyright string in a quick test, so I think there’s always a zero terminator there, which makes this our first “C-style string” in any of the UCSD p-System.

Code Segments

Immediately following the Segment Directory are the segments themselves. The structure of a segment looks something like this:

| Procedure code | Code & Attributes for a procedure |

| … | …repeated multiple times |

| Procedure Dictionary | ‘n’ pointers to the start of a procedure, one for each procedure |

| Procedure count & unit number | This tells you how many entries are in the dictionary, and which segment this is |

Decoding a code segment

Looking at the segment information in the example file, we get:

Segment 0x0, name: HELLOWOR, address: 0x01, length: 0x70, kind: Linked

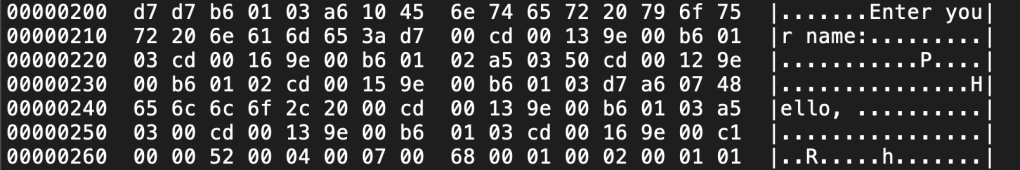

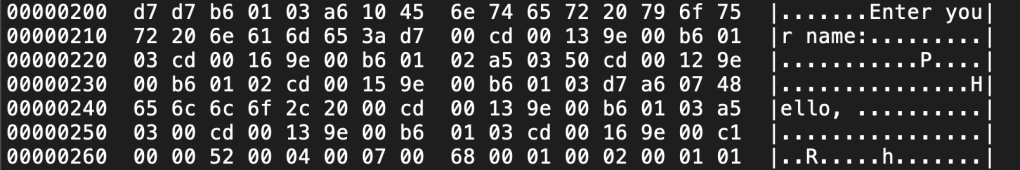

And, if we dump the 0x70 bytes starting at location 0x200 (because address is in blocks, we get:

That looks promising. Now, what is all that? This is, as it turns out, the actual p-Code (and string constants, apparently).

The “code” address provided in the segment directory is the start of the code. After the end of each of the code segments, there is a procedure dictionary, which gives you information about each of the procedures defined in that segment. But here, we only have the one procedure, the outer-most one, so we don’t need to look into the procedure dictionary, just yet.

Disassembly of the p-Code

Okay, let’s assume that this code segment starts with p-Code opcodes. What are they representing? Let’s take a look at the opcode table in the reference manual, and see what we get by manual disassembly of the first few bytes:

| Byte(s) | Opcode | Description | Notes |

| d7 | NOP | No-op | |

| d7 | NOP | No-op | |

| b6 01 03 | LOD 01 03 | Load intermediate word. Fetch word with offset 01 in the activation record found by traversing 03 Static Links, and push it. | Presumably the return address. We’ll look at the structure of activation records in a later post. |

| a6 10 | LSA 10 | Load constant string address. Push a byte pointer to the location containing the argument byte (10), and then skip IPC past 10 <chars>. | This is tailor-made for using Pascal strings. After executing this opcode, there’s a pointer on the stack pointing to the string’s length byte |

| d7 | NOP | No-op | |

| 00 | SLDC 0 | Short load one-word constant. For an instruction SLDC x, push the opcode, x with high byte zero. | Pushes 00, 00 onto the stack. |

| cd 00 12 | CXP 00, 12 | Call external procedure. Call procedure 12, in segment 00. | Presumably this is the call to writeln(). We can figure this out by walking external linking info, I suspect. |

That’s just about comprehensible, minus a few small details about what these various things like activation records actually are, and how the procedure directory works, and, and…

The Procedure Dictionary

…is not documented in what I would consider “a clear manner” in the Apple Pascal manual. There are diagrams, but they are very vague. No data structure definitions, this time. But we know from the diagram that the last bytes in the code segment, after the actual code, are the Procedure Dictionary.

The last two bytes in the segment are supposed to be “number of procedures in this segment”, and “this segment number”. For this example, they’re 01 01, which seems reasonable. In another file that I compiled with one segment and 5 procedures, it comes out as 01 05.

I guess that the intent here is that you then work backward, given the known number of procedures, to find the start of each entry in the dictionary? What a tremendous pain in the neck. They could have at least rounded it up to a nice interval, or something.

Okay, so starting from the bytes just in front of the last two bytes of the segment, each entry in the procedure dictionary is supposedly a “self-relative” pointer to the beginning of the code. Whatever that means. In our case it’s 02 00, which we can interpret as 0x0002, which – yeah, add that to the start of the code segment, and we get past the initial NOP instructions to the first “real” instruction.

What’s not clear at this point is what’s between the “actual code” and the procedure dictionary. Or, rather, it’s definitely the Jump Table and various Attributes of the procedure, but the manual is very vague on how you’d find that data.

What’s Next:

Before digging deeper into the object file format, I’m going to spend some time describing how the p-Machine works. And I’ll probably disassemble more code (hopefully not by hand).

Leave a comment