One of the things I did while I was on the Writing Excuses Retreat for 2023 was to start working with Twine, a system for writing interactive fiction. This was something I decided to try in an attempt to break out of some serious writer’s block. It (or the cruise and retreat) seems to have helped – I wrote a few thousand words of fiction on the retreat, which is more than I’ve written in the past two years or so, probably.

You can play the (short, kind of awkward) interactive story I wrote about writer’s block here, on My Tiny Games Page

Interactive fiction? What’s that?

If you were a kid who grew up in the 1980s, you were living in the glory days of Interactive Fiction, even if you didn’t know it at the time. You could go to the mall and hit the B. Dalton Bookseller and get one of the many Choose Your Own Adventure books, which allowed you to explore a fantasy of sci-fi world, making your own story along the way by your choices. Or, you could go over to the Babbages, pick up a copy of Zork for your home computer, and descend into the ruins to the Great Underground Empire, where you were likely to be eaten by a Grue.

Interactive Fiction is any kind of story where the reader determines how the story turns out, based on their decisions along the way. In some sense, every computer game is Interactive Fiction, but the term is most frequently used in the computer context to mean games that are heavy on reading, and light on reflexive joystick manipulation and button mashing.

So, Zork is definitely Interactive Fiction. Many computer RPGs are arguably Interactive Fiction. Most action games probably aren’t.

What’s Twine?

Twine is a tool for building interactive stories, more on the Choose Your Own Adventure model, rather than the Zork model, although you can create more-complicated types of interactions if you’re sufficiently-motivated.

You can make Twine games in your browser, for free, at Twinery.org. You can also play some example Twine games from that page as well. There are desktop “apps” which you can download there that are (basically) just the editor web page, wrapped up in an app.

How do you write a story in Twine?

To make a story in Twine, you write a bunch of text in passages, and link them together. For example, a single passage in a story might look like this:

# Sunlit Glade

You are in a sunlit clearing, deep in the forest. There is an enormous tree stump in the middle of the clearing, with a cute white bunny rabbit sitting on top of it, carefully watching you. What do you want to do?

[[Pet the bunny]], it looks so soft and fluffy!

[[Slowly back away]], since this is so *obviously* a trap.Running this in Twine gives you something that looks like the following:

You can click on either of the options, and it’ll take you to another passage, named either “Pet the bunny” or “Slowly back away”, respectively. And if you want to make a Choose Your Own Adventure type of story, that’s really all you have to know. The formatting above, where # makes a headline, and * surround italicized text, is called Markdown, and it’s very commonly-used in the nerdier parts of the Web. The [[double brackets]] around links is a common convention from Wiki software, which is where Twine picked it up from.

You can build a whole story this way, with links in passages that lead to other passages. Once you’re done, you can “Publish” it to a single HTML file, which you can then deploy on any web server. Annoyingly, my “personal” WordPress install makes it harder than it needs to be to add “plain” html pages to the WordPress-generated ones, so I ended up hosting “Blocked” on a GitHub pages site, since I already have a GitHub account.

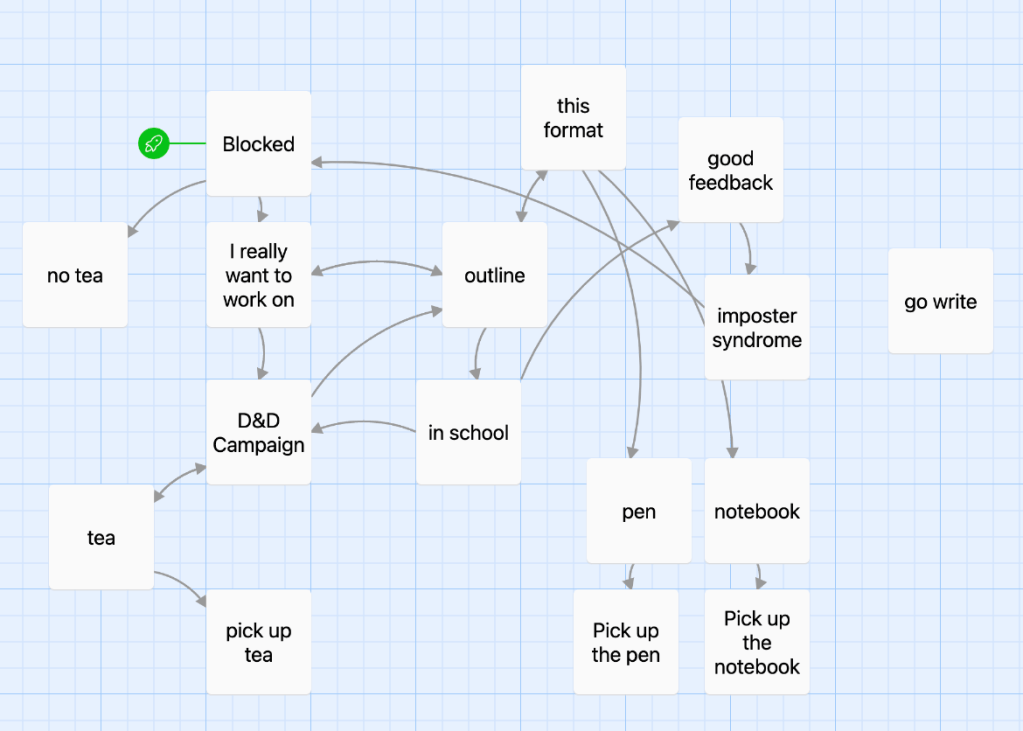

The Twine editor has some nice features, including a toolbar that will insert formatting codes from a menu, if you forget what’s _underscore_ and what’s *italics* or **bold**. And then there’s the really killer feature, at least for visual thinkers like me. It automatically generates a map of which passages have links to other passage:

Adding more-complex interactions

The more-observant of you will have noticed that not all of those passages connect to anywhere else, and you might be thinking they’re dead ends. Not so, generally. The “Blocked” story wants to have you repeat certain passages, but do things differently the second time. It’s got a minimal inventory system, where you can pick things up, and carry them with you. This involves writing some code, and the graph therefore doesn’t show all of the ways you can transition from one passage to another.

Code, eh? What kind of code?

This is where the story gets a bit muddy. Twine has a basic set of common formatting conventions based on Markdown, and a convention for how links are formatted. Doing anything more-complicated than that depends on your Twine Story Format, which is something like a combination of a document template and a custom programming language.

The default Twine editor comes with support for 4 different Story Formats, and they are vastly different in style, scope, and design philosophy. I wrote “Blocked” with Harlowe, which is the default story format for the current version of Twine. I do not recommend Harlowe, unless you’re just starting out, and you’re happy with a branching story with no persistent state. I felt like I was fighting against it the whole way, just trying to add small amounts of logic to the overall story flow. I will be trying the other formats for future projects.

Harlowe: where “Easy for non-programmers” meets Lisp Supremacy

So, what’s wrong with Harlowe? It’s intended to be a beginner-friendly format, but was clearly designed by a big-brained computer scientist type. Within a couple of paragraphs of the documentation, he’s talking about “macros”, “lambdas”, and “changers”, and how they can all be used to modify each other, and your story text. It’s not clear how all of these things interact, and while it’s nice to have support in the editor for inserting macro definitions from a dialog box, if something isn’t doing what you want, it can be difficult to understand why.

The syntax for all of this is…kind of awful? It’s obviously a Lisp-inspired language, which isn’t necessarily bad, but Lisps have a tendency towards simplicity of designing the language parser, rather than making them easy to read. In an attempt to make things easier for non-programmers, Harlowe has a bunch of “English-like” constructions, which are no more successful here than they are in languages like Applescript or SQL. So you can write either (set: $name to "Mark") or (put: "Mark" into $name), and that does the same thing. See? Easy for beginners! Don’t forget the : after the macro name, though, or either of the parentheses, or it won’t do anything, and in most cases, won’t give you any kind of error message.

One of the major changes in the newest version of Harlowe is removing the ability to mix Javascript into the macro definitions, which is certainly…a choice, for a system that authors web pages. The intent is that you shouldn’t need to use Javascript, and can just write any logic you need in their mutant proto-lisp. I’m not sure that’s really a great move. It also means that Google searches for “how do I do X in Harlowe?” will often return results for the previous version which don’t work at all in the current version.

The other Twine formats

As I mentioned, there are other story formats included with Twine (and even more formats available online). Of the ones included in Twine 2, we have:

Sugarcube

This was the previous default, and is the old man of the Twine formats. It’s more-complicated than Harlowe, but does more things out of the box. And there are a lot of people who’ve used it over the years, and have developed add-ons for various features.

Chapbook

A new “beginner friendly” format, by the author of Twine. This is new, feature-poor, and maybe not quite as polished as it could be, yet. I think it does a pretty good job of separating logic and text, and has some very-opinionated ideas about how to structure stories to make them maintainable. I think it’ll be really interesting in a couple of releases.

Snowman

This format fully-embraces Web technology. It doesn’t try to hide its HTML, CSS, and Javascript underpinnings. It’s deliberately bare-bones, providing basically nothing in the way of pre-built routines except some basic history and state manipulation. Anything you want to do beyond very basic linking and text formatting, you’ll be using JavaScript to do it. Probably the best choice for anyone who wants to try writing Interactive Fiction, and who already knows Web tech.

Non-Twine options

As I get further along in this journey, I intend to look at a couple of other options for IF authoring, including the following:

Ren’Py

Ren’Py is a Python-based platform for making Japanese-style Visual Novels. This is a very specific kind of story format, which I have relatively-little experience with. I really loved Doki Doki Literature Club though, which is a kind of deconstruction of the genre, incidentally also written in Ren’Py.

Inform

Remember Zork, up above? Inform is a parser fiction authoring platform, closely modeled on the Infocom games of the 1980s. In fact, Inform can generate code for the Z-machine virtual machine which Infocom created for all of those games. Recent versions also support a more-capable runtime model.

The Inform programming language takes the “natural language” direction to the extreme. Inform stories are written almost entirely in (somewhat stilted) English

Bitsy

Bitsy is an intentionally-limited game/experience making system. It’s not necessarily text-forward like the previous options, having bitmap graphics, sound, music, and limited animation. But it’s got an 8-bit aesthetic, and has been used to make games somewhat reminiscent of the old Zelda games on the Gameboy. Some really beautiful games have been made with it.

Pulp

Speaking of the Gameboy, there’s this extremely niche handheld black-and-white game console called the Playdate. You probably haven’t heard of it. But I’ve got one, and one of the development options for it is Pulp, which is a sort of Playdate version of Bitsy. It’s not exactly Bitsy, but it was clearly inspired by Bitsy. There’s an interesting pull towards the idea of being able to carry a story around in my pocket, and just whip it out and show it to someone.

Leave a comment